The Tofsee malware family attempts to evade detection by using a custom encryption protocol. Nonetheless, that protocol can be identified efficiently. This post describes the detector that I developed and implemented in mercury.

Why develop a detector for Tofsee, despite the fact that it is neither the newest nor nastiest malware? Because it is still infecting devices. When I went looking for custom encryption protocols in malware traffic, it was commonplace. Furthermore, studying non-standard malware protocols requires a process of elimination – filtering out Tofsee communication reveals other interesting malware. This post explains the detector and how it works, then offers observations and conclusions.

CERT Polska reverse-engineered Tofsee in 2016. I implemented the decryption algorithm per their specification, and found that worked on traffic generated by malware samples in 2023 and afterwards. In sandbox runs, the decrypted initial messages followed the expected fixed message structure, with valid IP addresses in the bot_ip field. Additionally, the unknown1 fields mostly consisted of zero bytes. Turning these observations into a detection algorithm results in the following logic, which is applied to the first message in a TCP session:

- If the message is not 200 bytes long, it is not Tofsee.

- If the decrypted message does not contain a low Hamming weight

unknown1field, it is not Tofsee. - If the decrypted message does not contain a valid IPv4 address in the

bot_ipfield, it is not Tofsee. - Otherwise, it is a Tofsee initial message.

The most common value unknown_1 field was 01000000010000000020030003000000 (hex), and all of the values appear to be an array of small unsigned integers. It is not clear if those integers are 8-bit values or 16-bit values, but the Hamming weight test doesn’t depend on the structure of that field, since it just counts the number of non-zero bits in the field.

A valid IPv4 address will not be equal to 0.0.0.0, which is reserved for special use. Verifying that the bot_ip field is valid prevents false positives that would otherwise occur due to a pathology of Tofsee’s encryption.

The custom encryption algorithm is essentially an autokey cipher in which the first 128 bytes of the plaintext message serve as a session key, and simple algorithm is applied to encrypt each byte successively. For our purposes, we need the decryption algorithm:

void decrypt(const uint8_t *ciphertext,

uint8_t *plaintext,

size_t data_len)

{

uint8_t res = 198;

for (size_t i=0; i<data_len; i++) {

uint8_t c = *ciphertext++;

*plaintext++ = res ^ rotl<5>(c);

res = c ^ 0xc6;

}

}

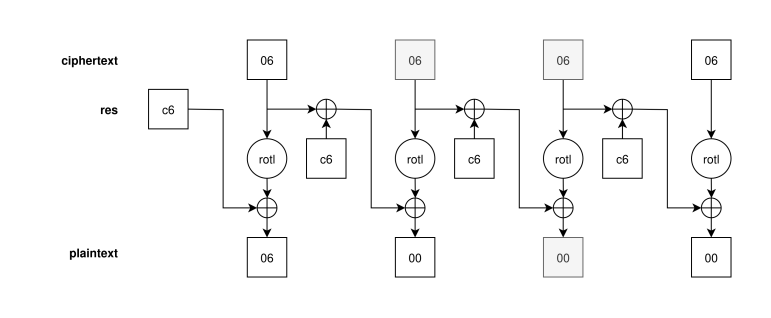

Here rotl<5>(c) returns the result of rotating c five bits to the left. This process is illustrated in the diagram at the top of the page, which shows ciphertext bytes (top row) being converted into plaintext bytes (bottom row). As is conventional, ⊕ denotes the exclusive-or operator.

Avoiding False Positives

The tofsee initial message detector can have false positives if the packet contains a run of repeated bytes with the value 0x06 or 0xf9. This is because of a quirk of the decryption function: if the ciphertext contains a run of those values, the plaintext will contain a run of zero bytes (because rotl<5>(c) == c ^ 0x06 for c=0x06 and c=0xf9). It also happens that the byte plaintext[i] depends only upon ciphertext[i] and ciphertext[i-1], as shown in the decryption algorithm diagram. (Trace the path from the two light gray ciphertext bytes to the light gray plaintext byte.) That is, decryption has low diffusion and error propagation, much like the Cipher Block Chaining block cipher mode of operation.

A run of zero plaintext bytes will pass Step 2 of the detector, because it will cause a low Hamming weight unknown1 field. Fortunately, a run of zero bytes often causes the bot_ip field to be invalid, causing it to fail at Step 3. Why do TCP initial messages with runs of 0x06 or 0xf9 occur? I’m not sure, but I’m not surprised. Lots of weird things show up in network data.

Optimization

What is the computational cost of our detection logic? Not much. For most non-Tofsee messages, it is extremely low, consisting of a check on the length of the TCP data field. For messages that pass the length check, the plaintext fields bot_ip and unknown1 must be decrypted so that the checks in Step 2 can be performed. The straightforward way to do this is do decrypt the entire 200 byte message, but there is a computationally cheaper method: decrypt only unknown1 and bot_ip, using our observation above about error propagation. Thus we need only decrypt twenty bytes to perform our checks.

Message Details

The plaintext of the initial message, as determined by CERT Polska’s reverse engineering, has the following fixed format (assuming a packed structure):

struct greeting {

uint8_t key[128]; // session key

uint8_t unknown1[16];

uint32_t bot_ip; // botnet IPv4 address

uint32_t srv_time;

uint8_t unknown2[48];

};

The names of the fields unknown1 and unknown2 reflects the uncertainty of the reverse engineers. Fortunately, there is enough predictability in the former field to enable reliable detection. In thousands of observations, the largest Hamming weight that occurred for that field was seven. If it were generated uniformly at random, its expected weight would be 64.

Observations

While I followed CERT Polska’s excellent description here, it might be more correct to say that Tofsee has an obfuscation algorithm rather than encryption algorithm. To paraphrase Mencken, the mechanism is so weak that it barely escapes not being an encryption algorithm at all. Presumably the design criteria of the malware authors were to obfuscate messages well enough that signature-based detection systems cannot detect them with regular expressions, while at the same time avoiding the need for cryptographic libraries. They achieved those goals, but fortunately for us, the decryption algorithm has extremely weak diffusion, making our trial decryption efficient.

Conclusions

The Tofsee communication detector works well. It is efficient, avoids false positives, and has zero false negatives on all of the traffic that I’ve seen so far. Besides being directly useful, these results suggest that it may be possible to develop custom detectors for other custom malware encryption protocols.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Adam Weller (for help running down false positives), Brandon Enright (for observing ROTL in the encryption algorithm), Apoorv Raj (for help implementing and integrating in mercury), and Blake Anderson (for large-scale observations).

Copyright © 2025 David McGrew and licensed under CC BY 4.0